The Invention of Morel (La Invención de Morel) by Adolfo Bioy Casares is a masterpiece of 20th century Latin American literature. Octavio Paz and Jorge Luis Borges describe the novella as “perfect.” Other admirers include Gabriel García Márquez, Julio Cortázar, and Alejo Carpentier. With its blend of detective fiction, realism, romance, science fiction, the fantastic, and the Gothic, some consider it the first instance of “magical realism.” But its influence extends far beyond Latin America.

Published in 1940, when Bioy was just 26 years old, this short novel anticipated the Latin American Boom of the ’60s and ’70s, our current “age of technological reproducibility” (holograms, VR, etc.), and some of the science fiction of Philip K. Dick, especially Ubik, which itself inspired movies like The Matrix and Inception, and most recently, WandaVision. Also, the TV show Lost was inspired by the story; in season 4, episode 4, James “Sawyer” Ford is seen reading the novel by Bioy Casares, causing fans everywhere to search the story for similarities (of which there are many).

It’s a quick read at less than 100 pages and even has illustrations by Jorge Luis Borges’s sister, Norah Borges. We highly recommend it. It’s set on an island and full of adventure, romance, and sci-fi. But don’t mistake it for beach reading. The text demands your full attention. And a rereading or two. Read it. Then return.

Sudden Light

I have been here before,

But when or how I cannot tell:

I know the grass beyond the door,

The sweet keen smell,

The sighing sound, the lights around the shore.

You have been mine before,—

How long ago I may not know:

But just when at that swallow’s soar

Your neck turn’d so,

Some veil did fall,—I knew it all of yore.

Has this been thus before?

And shall not thus time’s eddying flight

Still with our lives our love restore

In death’s despite,

And day and night yield one delight once more?

Jorge Luis Borges quotes this poem in the prologue

I first read this book when I was 19 and haven’t been able to get it out of my head since. Similar to The Turn of the Screw by Henry James, it’s full of ambiguity, allowing for multiple interpretations. With each reading, each repetition, a new meaning emerges.

Proceeding by suggestion rather than affirmation, Adolfo Bioy Casares’ fantastic novella The Invention of Morel (1940) leads the reader down multiple interpretive tracts. Written entirely in first-person diary entries by a fugitive from Caracas stranded on an island (à la Robert Louis Stevenson), the narrator tells us he has been falsely accused of a crime (not disclosed), causing him to flee to an island somewhere in the Pacific, “known to be the focal point of a mysterious disease.” The diary results in a “reality” of the text which is simply the “reality” of a subjective experience, an “unreliable narrator.”1

Thus, the story could be the invention itself, with the nameless narrator sometimes thinking that all this could be the delusional fabrication of his feverish imagination. The intentional ambiguity of the text (reflected in the double genitive of the title) reads like a detective story with the last page missing. The grammatical term, “double genitive,” also known as “double possessive,” makes it unclear whether the invention is Morel’s or if Morel is the invention.

First edition dust jacket cover

(By the way, the name Morel may have evoked a couple of things for you: H.G. Wells’ The Island of Dr. Moreau, the Morelli Method in Art History, Gustave Moreau, morels and mycology, etc.)

Despite some disjointed and questionable memories — often contradicted by the mysterious “editor” — we know very little about the narrator’s past life (what crime did he commit? who is chasing him?), but are told he is “a writer who has always wanted to live on a lonely island.” Bioy Casares’s use of an unknown paratextual editor is a literary tool, a textual machine, to increase verisimilitude (the impression of truth, reality, lifelikeness, in fiction), while at the same time casting the narrator in a dubious light.

Later, we learn that the narrator used to write for a literary magazine in Venezuela. Throughout the text, ghost stories are mentioned several times. “I dreaded an invasion of ghosts or, less likely, an invasion of the police.”

After a period of intense paranoia at having escaped imprisonment, the narrator begins to calm down, believing himself to be all alone on the island to work on his two books, Apology for Survivors and Tribute to Malthus. On the hundredth night, however, the narrator wakes up to loud “music and shouting” and discovers a crowd of people on the hillside “as if this were a summer resort like Los Teques or Marienbad” (10-11).2

Days pass and the apparitions continue to hang about the museum and swimming pool located in the center of the island, which had appeared abandoned at first. After many days of carefully observing these “odious intruders,” the narrator finds he is falling in love with Faustine — a gypsy-looking woman who likes to read and watch the sunset.

But it turns out that Faustine is also the object of Morel’s desire, causing a “mimetic desire”3 in the narrator, making Morel the “enemy” and Faustine only accessible through opposition with the other male force, who bears a striking similarity to the narrator (36). The problem? Faustine completely ignores the narrator, as does everyone else on the island.

“It was not as if she had not heard me, as if she had not seen me; rather it seemed that her ears were not used for hearing, that her eyes could not see” (28). Other things about the island caused him to feel estranged, like the presence of two moons and two suns, evoking an otherworldly, science-fiction-like setting. “Reality appears to be changed, unreal” (65).

Despite the various modes of interpretation, Bioy Casares implants key narrative devices to disrupt any kind of fixed interpretation, thus causing a kind of interpretative panic. Any definitiveness emerges from a misty phantasmagoria. The presence of the automaton-like people on the island causes the narrator to speculate:

Hypothesis 1: Experimentation with new roots (Mandrake/Ginger root?) combined with the oppressive heat has caused the narrator to hallucinate.

Hypothesis 2: Perhaps the people on the island are conducting an elaborate ploy to catch the fugitive and return him to justice.

Hypothesis 3: He has caught “the famous disease” associated with the island and has been imagining the people, Faustine, the music and is slowly decaying, “approaching death” (51-52).

Hypothesis 4: From a dream, the narrator gets the idea that he could be a patient at an insane asylum, where Morel is the director. “Sometimes I knew I was on the island; sometimes I thought I was in the insane asylum; sometimes I was the director of the insane asylum” (à la Caligari) (52).

Hypothesis 5: Like Dante, or some other traveler amidst the dead, the narrator thinks that he himself might be dead, thus explaining why he is invisible to the people on the island. Maybe the people he sees are dead too, but they exist on a different plane? “The thought delighted me. (I felt proud, I felt as if I were a character in a novel!) (53).

Always entertaining new possibilities, the narrator cannot help but impose his own inner world of desires onto the externalized projections. If we can trust the narrator, which is doubtful, the “real” explanation is revealed to him by Morel in a dramatic speech given to his guests.

This final hypothesis proves the most “realistic,” since it is a scientific, technological explanation, and also since it came straight from the mouth and notes4 of Morel:

“This is my latest invention. We shall live in this photograph forever. Imagine a stage on which our life during these seven days is acted out, complete in every detail. We are the actors. All our actions have been recorded” (66).

The images on the island are actually projections that Morel has recorded and transmitted, using a machine powered by the tides. Morel’s invention is actually three machines — a receiver (of waves and vibrations [tactile, thermal, olfactory, etc.]), a recorder (makes and stores the recordings), and a projector (projections received through space “whether it is day or night”). And when you synchronize all of the senses, Morel claims, something like consciousness emerges.

“When all the senses are synchronized, the soul emerges. That was to be expected” (71).

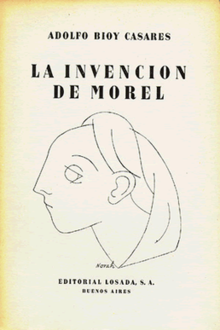

First edition cover with an illustration of Faustine

We are to achieve immortality through a recording of “the real.” In this way, both Morel’s invention and the narrator’s diary (Bioy Casares’s novella) achieve this end. A recording is a weapon used against the tragedy of a disappearance — a weapon against death itself.

“I examined the shelves in vain, hoping to find some books that would be useful for a research project I began before the trial (I believe we lose immortality because we have not conquered our opposition to death; we keep insisting on the primary, rudimentary ideal that the whole body should be kept alive. We should seek to preserve only the part that has to do with consciousness)” (14).

This passage, taken from an early diary entry, seems to provide a key clue for interpreting the narrator’s diary. Although everything is left quite vague, the narrator confesses that he had been researching a “project” concerning the survivability of the self after the death of the body before his trial.

This personal ideal — a transcendental dimension where the organic status of the body is seen as a hindrance — serves as one of main driving forces behind the unnamed narrator’s actions. The focus of both Morel and the narrator’s desire, however, is clearly the unattainable Faustine.

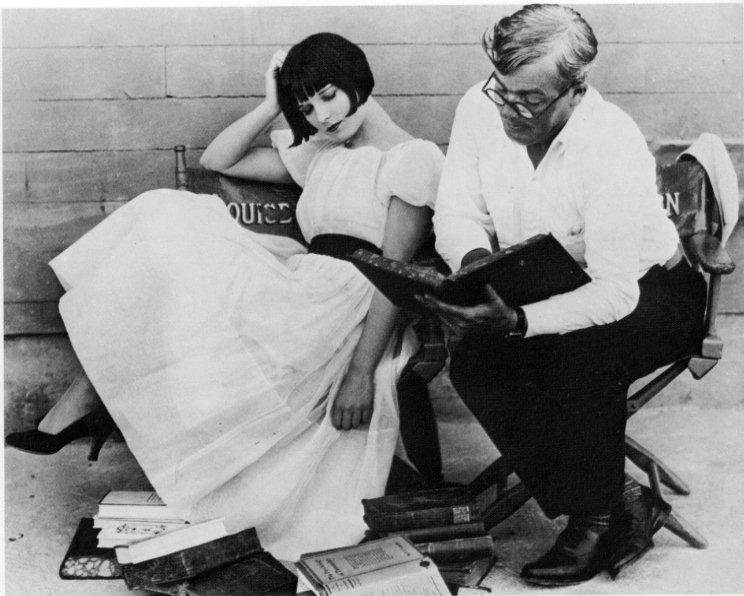

The three main men — Bioy Casares, Morel, and the narrator — desire Faustine (Faustine as a stand-in for Louise Brooks) and wish to invent and record memories with her in order to live with her eternally, on the same plane (like photoshopping your image with a celebrity).

The name Faustine evokes the term Faustian (meaning colloquially, “deal with the devil” or “devil’s contract”), which is exactly the type of deal both Morel and the narrator make — Faustine in exchange for their souls.

The real Faustine is impossible to attain. They must remain satisfied with a relationship with her image only and hope that some part of her consciousness will be recorded as well, to exist forever in loving contemplation.

The projection of Faustine (not Faustine herself) is the object of the narrator’s desire, and provides him with a hope for actualizing this desire through interaction with a machine (whether it be the machine on the island or the machine as diary/book). In both cases, the narrator must undergo a sort of death.

Faustine exists only within the narrator’s own virtual reality — the object (Faustine) is the reflective surface in which the narrator (subject) sees his own desires, fantasies, and dreams. Faustine projects another possible world for the narrator, an escape from the torture of being a ghost among ghosts, one in which he desperately wants to be a part of.

From the novel, one can also see how desire is both a creative and destructive force, which accumulates internally until it manifests itself in the external world. The possibility for this desire to take over “reality” and supplant it with a “fake” world filled with false impressions and sensations is suggested multiple times throughout the novella.

For example, one of the diary entries ends with an incomplete sentence — “This afternoon—“ — suggesting that the narrator was interrupted, had a memory lapse, or otherwise couldn’t finish the sentence (25). The nameless narrator undoes the relationship between inside and outside, pointing to the inner world of dreams to suggest a possible interpretation of his circumstances, nevertheless clinging to the hope that Faustine is real and does exist, if only someone in the future can unite “disjoined presences” (103).

When the thing itself emerges in the simulacrum, the original ceases to exists. When things get too exact (in copy), you lose the point or purpose of the original. If you cannot tell the difference between copy and original, does it matter which is which? Like the machine that simulates reality, the novel creates a true “looking” picture of the world, which seems real, but is not.

Through this elaborately designed trompe l‘oeil, where reality and fiction confound each other, one can see how The Invention of Morel uses both fiction and science to fabulate new technologies and new possibilities of being, playing with various strategies of 19th century literary realism.

Although the science is fictionalized, it is based on a theoretical possibility and parallels its real, otherworldly scientific rigor, thus making us want to believe that Morel’s machine is actually real, and what the narrator is telling us is true.

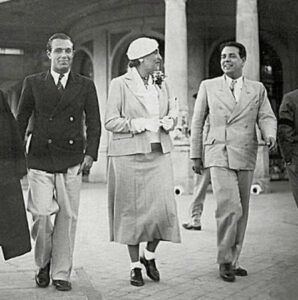

Bioy Casares with Victoria Ocampo and Jorge Luis Borges, en Mar del Plata, imagen del fotógrafo Enrico Miagro

Underwriting such beliefs, however, is a battle of possibilities and transformations — a certain grappling for truth albeit without finding any. When the narrator dies at the end of the book, his soul is presumably transferred into the recorded image he had created of himself. Rather than feeling that the character died, one gets the rather refreshing feeling that this is not his finality, but rather the beginning of his endless recurrence in both text and image, through the miraculous cinematographic and writing apparatus that preserves him with Faustine and Morel (80).

The narrator’s disappearance is not a death, but the beginning of an endless return. His diary and his recording, filled with the eternal contemplation of an unrequited love, creates a virtual reality to be repeated again and again — the once more of an endless becoming. Did Morel achieve his goal of immortality? Did the narrator? Only time will tell.

References:

-

The literary device known as the “unreliable narrator” was first coined in 1961 by Wayne C. Booth in The Rhetoric of Fiction. Unreliable narrators in works such as Turn of the Screw and Fight Club force readers to reconsider their interpretation of the story and consider all the implications of each hypothesis. These works play with the reader, forcing a disturbing confrontation with ambiguity, a psychological dis-ease. William Empson’s Seven Types of Ambiguity defines “ambiguity” in two ways: 1) “a puzzle as to what the author meant” and 2) “any verbal nuance, however slight, which gives room for alternative reactions to the same piece of language” (Empson 19). Complicating things further, “ambiguity” itself is ambiguous, difficult to define and pin down. As the title of Empson’s book indicates, he presents the reader with seven different types of ambiguity, too many to describe here. Not to get political, but it’s interesting to note that conservatives are less comfortable with ambiguity than liberals.

- Los Teques is the capital of the Venezuelan state of Miranda and Marienbad is a spa town in the Czech Republic. It’s worth noting that Alain Resnais’s equally dreamy and enigmatic film Last Year at Marienbad (1961) probably took inspiration from Bioy Casares.

-

The term “mimetic desire” (all of our desires are borrowed from other people) comes from René Girard’s mimetic theory, expressed in Deceit, Desire, and the Novel: Self and Other in Literary Structure. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1965.

-

The editor’s note tells us that Morel’s original notes have been marked off with quotation marks in the text while “the marginal notes, written in pencil and in the same handwriting as the rest of the diary, are not set off by quotes” (65). This use of crosstextuality to dramatize the checking of a text for accuracy reflects “the found manuscript” literary device used in old Gothic novels (i.e. Dracula, The Manuscript Found in Saragossa, etc.).

-

Bioy Casares was admittedly in love with Louise Brooks, the silent film actress – based Faustine off of Brooks – initial buildup is all dream like – they are all photographs, the people – extremely sophisticated photographs that can capture the image and physical essence, depth of being a human being – a film if it was three dimensional and captured actual physical objects and then replay.

Additional Reading/Watching

Italian 1974 Full Movie (by Emidio Greco) with eng subtitle :

part one: https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x17uyyq

part two: https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x17v42h